Audio cable design - Developing the Experience range of audio interconnects and speaker cables

27th December 2018

How the Experience range of audio interconnects and speaker cables were developed

This is a slightly modified version of the article that appeared in HiFi Critic December 2018.

The relationship between conductors in an audio cable affects the musical presentation of a hifi system.

Because we stand at the center of our own point of view, Douglas Adams observed we can end up seeing the world like a puddle would, waking up in the morning and thinking: “this hole suits me rather neatly it must have been made to have me in it”. The reaction to holes getting filled in or puddles evaporating proved interesting, when Wire on Wire launched its REDpurl™ Adaptive Geometry*.

One industry stalwart averred that cables had been around too long to accommodate new ideas from upstarts like us; another rather bizarrely remarked that if anyone was going to invent something different it should be an American!

New ideas it seems do nothing for the blood pressure but they have addressed the two beefs I had a few years back as an audio enthusiast: first the failure to explain in cable reviews how different materials and geometries affect the presentation of audio recordings; secondly, why every ‘highly recommended’ cable that I ever bought seemed to be at least one tweak away from musical nirvana!

Some research was clearly needed back then, and this was to highlight, amongst other things, the important role that geometry (whether the cables are co-axial, twisted, woven, etc.) plays in the way music is presented. The findings were published in a 2008 article The Idiot’s Guide To Cables (HIFICRITIC Vol2, No6), which eventually (rather unexpectedly) led to the setting up of a new audio company.

One of those experiments involved comparing tightly and loosely twisted pairs of wires (of equal length). Physics tells us that as conductors come closer to each other the capacitance increases (even more so as the twist-rate increases), but it doesn’t tell us how this affects the sound presentation?

In the highly twisted samples musical images appeared more discrete and were pushed towards the back of the soundstage, whereas looser windings presented larger, sometimes overlapping images closer to the listener. The former sounded a little drier whilst the latter sounded more ‘open’ with a greater sense of air and space.

Geometry clearly had a significant effect on presentation, yet the difference in capacitance between the two was not great: 34pF in the more tightly wound cable, against 29pF in the other.

It is important to note there had been no change in recorded detail during these tests only in the overall presentation but once observed, a difference creates a preference.

I liked the more open sound, whilst others in the test team preferred the punchier, flatter sound of a more tightly wound cable. The ideal might be to please both tribes (and those in between), without having to buy a host of different cables, but at this stage there was no notion of a solution, short of adding electronic components to the system.

However, what we could all agree on was that none of us much liked the cable’s presentation, which seemed to favour upper frequencies at the expense of bass reach and weight.

Cable conductors influence tonal balance

While keeping insulation, conducting materials and geometry constant, different conductor gauges were used: all sounded different in the one significant respect, that of tonal balance. The larger the wire gauge, the darker the overall tone became, with more reach and weight in the bass but a less discernible high-frequency presence. Dynamic expression improved, and images felt fuller, more three-dimensional and easier on the ears but again the balance was wrong without the higher registers.

Smaller gauge conductors, on the other hand, seemed to provide more detail, delivering fine nuances, especially at upper frequencies. On the Freddie Hubbard album Hub-Tones, Reggie Workman’s fingers could be heard working the strings of his bass more clearly, for example, but with a somewhat two-dimensional presentation and a lack of bass weight.

Listening to these different cables it was easy to see how musical detail can be confused with brightness and we wanted the former. A conductor with a tonal balance that favours upper, brighter, frequencies can initially give the impression of detail. So, a voice can sound clear and sharp but paradoxically, words can be difficult to pick out, whereas a tonally darker, thicker wire improves vocal clarity by enhancing the mid-band. A sure sign of imbalance is when one finds oneself constantly turning up the volume of a bright sound because detail seems to be lacking.

The way ahead seemed clear at this stage; to achieve the best sound, we needed to use different gauge conductors, but there was a problem. Pairs of wires sounded great on their own but when we combined them using conventional techniques, the resulting sound always lacked a sense of natural flow. In short, we now faced a Torrance test of creative thinking: how many unique responses to a challenge with no fixed right answer could we come up with?

Challenging the ‘tried and tested’ to take audio cable design forward

The answers started to emerge when a past article in the audio press came our way. It observed how much better amplifier prototypes sounded before the engineers had bundled together the internal wiring into neat symmetrical bundles. Was neatness the enemy of musicality? We began to move away from a symmetrical arrangement of parallel wires (with their attendant crosstalk and resonant modes).

The idea of a random arrangements of loose wires that didn’t allow identical conversations along the length of the cable was beginning to appeal. We tried a few ideas and it seemed that things just sounded better when wires were kept kind of messy!

Although a bunch of wires can sound good, it’s never the same from one batch to another, and they look like something that happens when a fly gets into your cubicle when you are teleporting (and we all know how that ended…). However, the idea that it was OK to look at looser configurations pushed us towards braiding techniques that created a more open structure. While we were not the first to think along these lines, we feel we were the first in holding firmly to the idea of a cable capable of adaptability.

Challenging the ‘tried and tested’ of any profession is never going to be easy and cable manufacturing is no exception. Produce something that is not tube-like (although flat and woven do figure) and eyebrows are raised. But these shapes, which have changed little over the years, are not created in the interest of good HiFi, but are imposed by the machines that braid, twist and weave wires. Machines can produce miles of cable cheaply but they have their limitations.

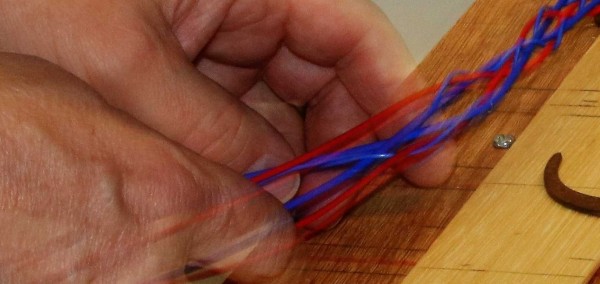

In contrast, hand-braiding allows us to depart from industry standards, so a cable’s shape is now limited only by the physical properties of the materials, the imagination, and, most importantly, by the ear.

Wires may not have feelings, but they do have what those in the industry describe as ‘memory’. Bend them one way and they want to go another. They can twist round and give you a nasty poke without warning if you don’t watch them. They resist change in different ways depending on their structure and insulation (machines overcome these problems with force). The dialogue that develops between these materials and the human hand, eye and ear results in a craftsmanship that enables the wires to be guided into their ideal alignment.

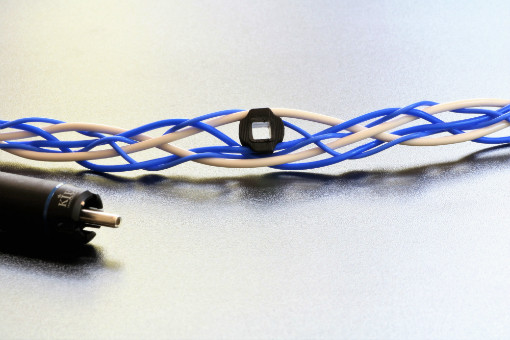

Using a craft driven approach and countless attempts, we finally found a cable geometry that got us excited. A braided design, notably organic in shape with the wires forming an open asymmetric structure. Separated from each other, these wires crossed each other at different angles, preventing parallel arrangements, inhibiting crosstalk, and keeping capacitance low. An asymmetric lay created by conductors of different lengths helped address issues of harmonic modes across the music spectrum. Its open structure was stable without the need for supporting and packing material.

The cable also had a striking aesthetic unlike any other cable, which we deliberately drew attention to with the use of different coloured PTFE insulation.

An open audio cable geometry can have its electrical properties tuned

The interconnects also turned out to be very tactile, so it didn’t take long before we realised we could hear more air and space in the presentation if we pulled one of the cable’s loops apart. This initially took us by surprise because the cables were sonically stable with general handling but sure enough loop separation did alter the sound presentation.

This makes sense if one looks at the loops in our cable design as a series of distinct circuits, each with their own capacitance, inductance and resistance. By inserting a spacer into one of these loops to tune it, the cable’s capacitance decreases by 1.4% and the presentation changes.

We now had what appeared to be a tuneable or adaptive design prototype. A cable with all the technical qualities we were after, which was also capable of being adapted or tweaked to suit different systems and ears and which we later termed REDpurl™ Adaptive Geometry.

Making sure an audio cable sounds at its best is an art based on science

Creativity may be defined as problem solving in an unexpected, useful and novel way but this doesn’t stop with the prototype. The really hard work is making that idea work for the market place in terms of re-design and fine tuning.

One of the more difficult parts comes in voicing the product, which is an auditioning process that has much in common with the artistic or creative experience. The cable designer must ask the question: “Is my invention finished?”

This problem of objectivity was addressed recently by music producer William Orbit and portrait painter Jonathan Yeo, on BBC Radio Four’s Only Artists. Yeo and Orbit talked about the techniques they use to monitor the success of their projects they’re working on. Yeo found that looking at one of his portraits for too long made any mistakes invisible, so he looks at it in a mirror to make it unfamiliar again. Orbit agreed; he was suspicious of anything he considered the best (or even the worst) in the world, performing Yeo's mirror equivalent by running the music backwards, putting on headphones the wrong way round, listening from another room, or letting other people listen.

We use the same approach, changing perspectives until we think we have nudged the brain into appreciating what is really there as opposed to what the ego is telling us. Wives, brothers and friends can be very direct in this regard, in pointing out ‘obvious’ problems. Irritatingly, they are usually right.

One final piece of the jigsaw was the decision concerning shielding. For many it must seem like an obvious requirement, until the question is posed: “Do you prefer the sound of your cable with or without RFI protection?” If you can hear a hum you will need one; otherwise there are other considerations.

Our earlier experiments pointed the way. We had arranged twisted pairs of wires running through 0.5cm diameter plastic tubes with different types of shielding applied to the outside. Although it was possible to hear a lifting of veiling and a darker background, there were also negatives. For example, shielding could lead to mid-band hardening that became more obvious the closer it was placed to the conductors. A dark background may be viewed as a virtuous absence of interference, but it can also interfere with the timing, making musical images sluggish.

Conclusions

Can we produce the perfect audio cable through geometry alone? The short answer is “no”, as detail also depends on the type and quality of the conductors. We achieve this in our Experience range of cables using silver-plated copper with PTFE insulation: conductors that are capable of teasing out the finest details without hardness (In our experience the reason why such conductors are sometimes accused of presenting a hard edge to recordings is down to poor cable geometry, not the conducting material itself.)

But cables live or die according to how they present this material. So, the flexibility of our design means mid-band detail can be highlighted or softened by altering a cable’s geometry to suit an individual’s taste and equipment. Opening specific loops can allow more air and space into a recording, enlarging the soundstage and the musical images, and creating a more immersive experience with greater solidity to the images. Some loops in contrast have little or no effect on the presentation. We have used this knowledge to simplify the tuning process, so users get the best out of their systems with a minimum of effort. (For some, the non-tuned version straight out of the box can be the best choice.)

We are still exploring our design’s potential with the help of our customers who point us towards aspects we have overlooked. After all, what fascinated Douglas Adams about the human race (when it wasn’t sitting around in puddles) was its enormous propensity for inventing things; not just exotic stuff like computers and jet engines, but also simpler things like corkscrews and bath taps. He might well have added cables: long may that continue…

* EU Registered Design No. 002544171, UK patent pending GB1602578.5

© C J Bell

This is a slightly modified version of the article that appeared in HiFi Critic December 2018.